UK Surveillance Data - A First Look

Recent data from the UK shows the oldest populations stand to receive the most visible benefits from COVID-19 vaccination. By far.

After writing Lies, Damned Lies, and Vaccine Statistics I found myself receiving a little heat. The criticism I received came in two varieties: Those who didn’t understand the distinction between the efficacy numbers and infection/case fatality rates, and those who understood but were upset that I had reported on and focused on numbers that didn’t seem to praise the vaccines.

The main focus on that article involved the public-facing health experts, misinterpreting a large study, making claims that the vaccines reduced the probability of death after infection near 100x. My article demonstrated that those calculations had not been performed in that large study, and when you performed those calculations, except for the oldest age group, the results were too ambiguous to make after-infection claims.

Some of what I will be analyzing today might require some familiarity with that initial article, so if you have not read that article please consider doing so. I will reexplain some important concepts here when necessary, but they will be far less thorough.

The weeks that followed

A short while later, I released a crude-prediction model estimating COVID deaths in Israel two weeks out, using only the current observed case numbers. During the initial prediction window1, the model was unfortunately accurate enough that the observed COVID death numbers were mostly within the prediction bounds. People noticed.

After I released my Israeli crude-prediction article, many more people noticed that things were a bit askew in that area of the world - out of line with the promises that health officials were making. During that time, I started to get some criticism that I was ignoring some supposed large body of evidence that “contradicted” me.

It wasn’t really possible for evidence to “contradict” anything I had said - since all I’d done is analyze the data people were using to demonstrate the data didn’t support the claims they were making.

What they should have said, instead, was that they thought new datasets existed that may have allowed someone to do the same analysis I had done in the original article using different populations and perhaps not result in the same ambiguity. They never pointed me in the direction of these datasets, however. They just said I was ignoring them.

Finally, some new data

Somewhere around Friday, September 10th, however, a dataset did come out of the UK, with a similar analysis that I had done with the Israeli data, with more diverse age break downs.

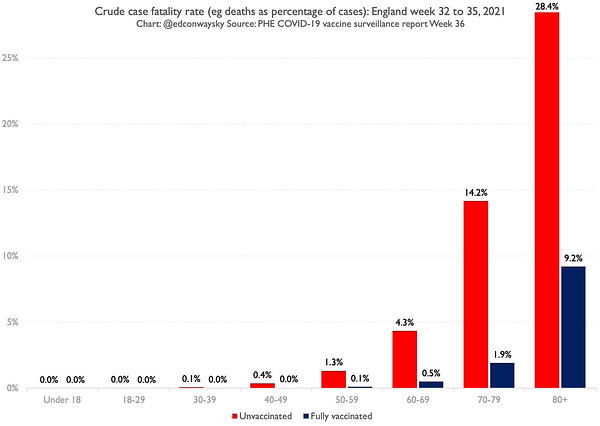

I had a few people send me the above tweet, asking me if it was accurate. I was delighted to see that the graph above was based on case fatality rates and not the “efficacy” numbers. These (case fatality rates) are the numbers almost everyone actually cares about.

I was less happy when I began to read the report and came across this line (emphasis mine)

This week, for the first time we present data on COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths by vaccination status

Although my reason for being annoyed at this line is partially personal, there is a large portion that is based on principle. The vaccination campaign in the UK started in December of 2020, around the same time it started in the United States, and only now did they start to provide reports that might provide the data people actually care about. The personal component is simply how much flack I took while the UK was twiddling their thumbs waiting until the fourth quarter of 2021 to release the kinds of data I wanted.

But enough complaining, let’s begin a deep dive. If all you want to know is if the graph in the tweet is accurate, it is. It reflects the data of the report. There is a lot more to get into though, to understand a broader picture, along with some important implications to discuss.

The vaccination campaign and the variants

The UK began its vaccine campaign on December 8th, 2020, while cases were still rising to their highest levels ever (at the time). Quickly after the new year began, cases started to plummet. Many were optimistic that if enough of the population could be vaccinated, cases would remain low and the pandemic of 2020 would be effectively over.

As we’ve all heard and probably seen to some degree, the Delta variant has thrown somewhat of a curveball at those expectations. So we will look at how the variant situation evolved during the vaccine rollout.

Alpha, B.1.1.7

The UK has been tracking coronavirus variants and has been releasing “Variants of Concern” briefings at regular intervals since December 2020. The first variant of major focus in these reports was the Alpha variant, which has three different names in the reports: Alpha, VOC-20DEC-01, and B.1.1.7.

VOC stands for Variant of Concern (in contrast to Variant under Investigation, which is a lower status), and the date represents, roughly, the date the variant was first tracked in the UK.

B.1.1.7 is a more universally meaningful name, that includes information about the variants genetic lineage. The naming convention can be thought of as being similar to computer software and the following graph can help visualize how it works.

By the 8th report in March, the Alpha variant was dominant, with others being tracked totaling less than a percent of all other cases.

Delta, B.1.617.2

Delta first appeared in Technical Briefing 9, the very next report, as B.1.617.2, with a status of “monitoring.” Technical Briefing 10 (with data up to April 22nd) gave Delta its informal name of VOC-21APR02, and began to include case numbers. Cases had plummeted by this point, and were nearing a bottom.

Soon after, in May, it became fairly easy for Delta to replace the Alpha variant and become dominant as cases began to climb.

As of today, Delta is still the main variant in the UK.

“Cases are decoupled from deaths”

When cases began to spike, the population level COVID deaths did not rise as they had in the previous wave.

The deaths in the above graph are scaled to be roughly equal to cases visually so the current divergence can be clearly seen. Because the deaths (thankfully) did not climb in the same proportion as the previous wave, people started using the phrase “cases are decoupled from deaths” which sparked me to write an article of a similar name.

The results in the UK were in contrast to Israel, where COVID deaths initially did rise in roughly the same proportion as previous waves. There appears to be a straight forward reason for the two countries to have significantly different results.

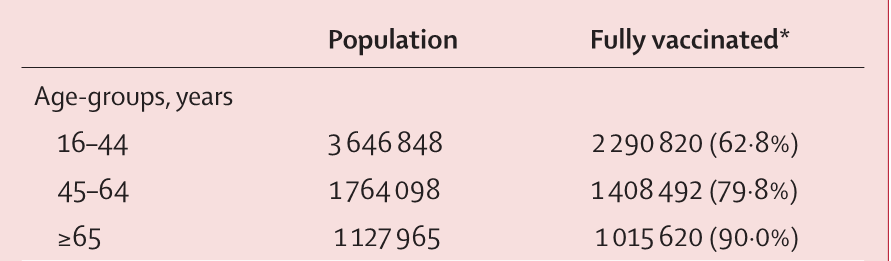

Israel has population of around 6.5 million age 16 and older, and a total population of around 9 million. The UK has a total population of around 66 million with a population of about 54 million ages 16 and above. Israel was simply able to vaccinate a larger percentage of their population per age group than the UK. By April 3rd, 2021 62.8% of the 16-44 age group was fully vaccinated.

The UK focused heavily on the elderly during their rollout, with the younger populations having only a few fully vaccinated by the same time period (Week 14).

This resulted in a strong reduction in cases for the older populations, where COVID death rates are the highest, and a relative explosion in cases for the youngest population, where COVID death rates are nearly zero.

I mentioned this scenario in the Israeli crude-prediction article as a possible outcome.

It should also fail dramatically if the infections are consolidating in the unvaccinated younger ages who rarely die.

The new report

Now that we have a general handle on the big picture in the UK, we can start to look at the data in the new surveillance report. It appears the data we are looking at today is going to be available every week in these reports at least for the foreseeable future. We will be looking at the data from the first such report, week 36, which covers weeks 32-35. Weeks 32-35 are Aug 8th through Sept 4th.

These reports are able to identify all cases and deaths during the time period and separate them by age and vaccination status. Thankfully, the age break downs are very refined.

The first thing we can note is that overall, 75% of the COVID deaths are consolidated in the vaccinated population (at least one dose). The unvaccinated population accounted for 25% of the COVID deaths.

But the unvaccinated were a larger proportion of cases at 35%

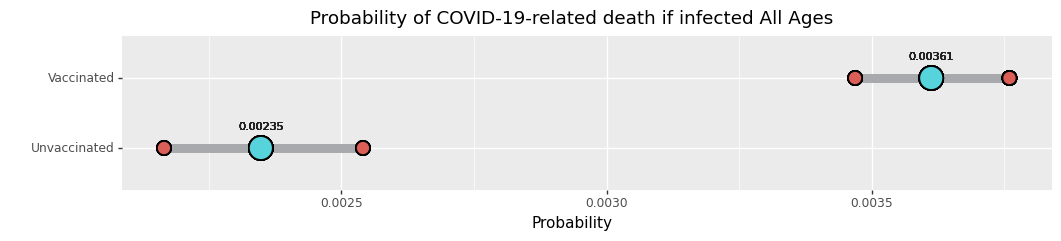

This brings us to a result that readers should be very familiar with by now: the case fatality rate for the whole population is higher in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated2.

Vaccinated from here on means 14 days after receiving the second dose. These results do not include the 1 dose population.

This result, like in previous analyses, is due to the vaccinated group preventing or not including (due to lack of vaccination) many infections in ages where COVID death rates are very low - leaving breakthrough cases in ages where the case fatality rates are higher to make up most of the results. The unvaccinated group has many thousands of cases in age groups that simply do not die in large numbers.

Age based case fatality rates

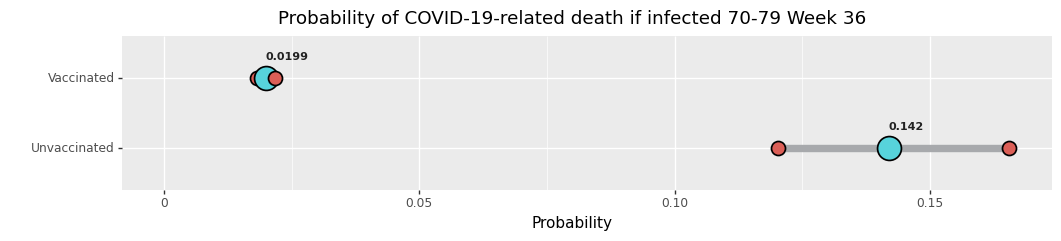

Just like the Israeli study I first looked into in July, the observed case fatality rate is lower in the vaccinated older populations. Be aware that while the visual width of these graphs are the same, the actual scale is not. Please pay careful attention to the x-axis and the numbers above the median (blue dot).

In contrast to the Israel study, because this data was collected during a surge, we have many cases, and unfortunately many deaths (comparatively), in each age bracket. This allows us to get estimates that we didn’t have before.

This graph has an odd looking number “4.02e-05.” This is a number formatting option meant to make very small numbers more compact. To be honest I couldn’t figure out quickly enough how to turn it off, and I was already at the point I felt this article was delayed too much, so I just left it that way. The full number is 0.0000402, with four zeros after the decimal point, contrasted with three zeros in the unvaccinated number.

The only age group where there was insufficient data to make a strong comparison was the Under 18 group.

The number of cases and deaths in the vaccinated group is simply too small to get a good estimate for comparison.

Be careful jumping to conclusions

These results, in some manner of speaking, are good. Everyone wishes for fewer people to die. But there are still many factors involved that do not permit us to simply say the vaccines cause a reduction in COVID death after infection. There are ways the vaccines could be the cause of a reduction in COVID death, and many they would not be.

Controlling for variants

If a variant emerges that is less lethal than others, but also causes an increase in breakthrough cases, that could create a situation where the unvaccinated population, getting a wide mixture of variants, has a higher case fatality rate than the vaccinated who are only getting the less lethal variant.

In this scenario, the being vaccinated changes what variant you would be infected with, and therefore could be said to cause your chance of COVID death to be lower if you get infected.

But this is a different kind of causal relationship than one usually imagines, because were a breakthrough variant to be more deadly, one would not be quick to say the vaccines cause increased chances of COVID death if infected, because it’s the virus doing the damage - the vaccine offered protection against infection for most things but this variant that didn’t exist some time in the past.

In this UK data, as we saw earlier in the analysis, the Delta variant is currently the only game in town, so this scenario does not apply here to the best of our knowledge. Unvaccinated and vaccinated people are getting the same variant. This could change if a new variant arises and should be remembered.

Population differences

A major ambiguity in these data sets, that does still exist in this UK data, is the question of people previously infected.

The CDC says

If I have already had COVID-19 and recovered, do I still need to get vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine?

Yes, you should be vaccinated regardless of whether you already had COVID-19…

And the NHS says

Should people who have already had COVID-19 get vaccinated?

Yes, they should get vaccinated. There is no evidence of any safety concerns from vaccinating individuals with a past history of COVID-19 infection, or with detectable COVID-19 antibody so people who have had COVID-19 disease (whether confirmed or suspected) can still receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

You can have the vaccine 28 days after you had a positive test for COVID-19 or 28 days after your symptoms started, so you may need to wait.

There is no good information in these data sets to indicate how those with previous COVID infection who have recovered interact with the case fatality rates. We don’t have case and COVID death numbers for

Unvaccinated never infected

Unvaccinated previously infected

Vaccinated never infected

Vaccinated previously infected

Because we do not have this information, we do not know if or by how much the numbers are influenced by those sub populations.

Populations differences of another kind

It’s not generally true that a person has a chance of dying from COVID. Not only is survival a result of many factors, some more able to be controlled than others, many people just do not have certain comorbidities that make COVID deadly. Looking at ages and gathering this information is very helpful - but it is not correct to say the mere fact someone belongs to an age group gives them a probability of dying from COVID. Probability statements like the ones we are making involve the fact we do not know enough to predict exactly who would die and who would survive. If we did, we wouldn’t need probability.

We do not know to what degree we are observing, broadly speaking, healthier people getting COVID in the vaccinated groups than in the unvaccinated groups. Since we see a difference for almost every age group except Under 18, it seems very unlikely that all of the difference could be due to such a “health imbalance” between groups. But because we do not know more it is certainly possible certain sub population medical differences change the observed fatality rates.

This unknown could swing both ways - if we knew we could even find out the vaccinated case fatality rates were lower than we currently observe.

The ideal

The ideal situation, which we simply cannot know just from looking at data like this, is that vaccination, even if a variant is able to cause a breakthrough case, for most people “preps” their immune system to fight the virus off, and is the main contributor to their increased chances of survival.

It may be the case that this is happening and causes the data we observe. Maybe previously infected people, in either the unvaccinated or vaccinated groups, do not get infected enough to affect the results we see. But simply seeing these results is insufficient to know conclusively.

Assume the ideal

As long as we acknowledge that we do not know for certain that these observations are caused by the vaccine in this ideal way, we can still assume they are and do further analysis to see what the implications might be. This is a perfectly valid and useful thing to do.

One final word of caution

The case fatality rates we’ve assessed here are volatile. We are not able to track individual people to see which individuals recovered and which died. Some of the cases in this dataset may be newer (becoming cases in week 35, perhaps) and the deaths may not be until a future report.

If cases are increasing during the time period, then we will over-count cases and under-count COVID deaths, reducing our calculated case fatality rates. Likewise, if cases are declining during the time period, we will be under-counting cases and over-counting COVID deaths, increasing the case fatality rate.

To demonstrate just how widely these four week snapshots can cause the case fatality rate estimates to vary, consider if we took 4 week estimates like this every week throughout the pandemic for the age group 80-84.

Even when the estimates are narrow, they can fluctuate wildly because four week snapshots like this simply do not connect cases to deaths for the same individuals. They only connect a time period.

This doesn’t prevent us from using these numbers but one needs to keep in mind that these estimates can and will change. We will want to redo the analysis to come with more refined numbers, in the future.

Saving lives: bang for your buck

Taking into account all the previous warnings: we can’t say for sure the vaccines cause the observed lower COVID death rates in the ideal way; we know that these estimates may be volatile due to the four week snapshot nature - we can assume that the vaccines do indeed reduce the probability of COVID death as we observed and also assume the future rates will be similar enough to our current estimates.

If we make those assumptions, we can take the data from the week 36 report and see how many lives we can save for every ten thousand full vaccinations, assuming they will someday have a breakthrough case.

We arrive at these numbers by taking our observed case fatality rates for both the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, calculate how many would die per 10 thousand people (95% probability range), and take the difference. In other words, if we had 10 thousand people, how many of them would die if they got COVID and were not vaccinated, and how many of them would die if they got COVID and were vaccinated. We then appropriately subtract the ranges to get best-case and worst-case estimates (95% probability) for the “deaths prevented” by the vaccine.

Previously we said that the case/death numbers for Under 18 were too few to make a good estimate. Here we are simply using an assumption that some or all COVID deaths predicted in the unvaccinated population could be avoided. We are choosing to assume the trend observed in older populations continues in the Under 18 group. This was a choice; the data did not change to give us this estimate.

The unvaccinated in the UK

The previous graph seems to indicate that the UK focused its initial vaccination efforts wisely, targeting the oldest populations first, as this is where, by far, the biggest per-dose bang-for-your-buck can be seen in terms of prevention of death. But we’re no longer at the start of a vaccination campaign. We’re 3/4 of a year into one. Over 90% of the older populations have been vaccinated, and some middle age populations well over 50%.

What does this perspective say about the remaining population3?

The numbers in red, “X People,” indicate the unvaccinated population of the age group. The lower and upper numbers of the bars, just as before, indicate the estimated lives saved by fully vaccinating everyone remaining in the age group.

In words, fully vaccinating 338 thousand people over 80 years old could save between 50-80 thousand lives, while vaccinating the remaining 12 million people Under 18 could save between 0-710 lives. The difference in lives saved is very dramatic.

To see just how dramatic, we can rollup all those under 70 years of age and compare.

In words, fully vaccinating 231 thousand people between 70-79 years old could save about the same number of lives as vaccinating the nearly 23 million people under 70.

Final thoughts

It may be surprising that despite the older population having such a high percentage vaccination rate that there is still such a large opportunity available to save lives simply by vaccinating people in those age groups. But COVID is simply not as lethal to younger people.

Deaths that do occur in younger age groups typically have multiple comorbidities4 and other markers that aid in identifying who among those age groups may be most at risk of death from COVID. Not everyone in those age groups is equally susceptible to death if they get COVID. It may certainly be possible to identify those sub populations and encourage them to get vaccinated, instead of hoping they get vaccinated in the attempt to vaccinate the entire population. There is probably a lot of low hanging fruit in the form of lives saved if people focus their attention and efforts. Saving those 710 kids under 18 years old may be a much smaller project than vaccinating 12 million people. You may be able to narrow it down to a few thousand likely candidates.

However, death is not the only negative outcome of COVID, and this data does not (and therefore neither does this analysis) contain information that may affect every individual. Long COVID may be a big deal - I do not have data on hand to make any claims about rates of long COVID. This analysis should not be treated as having investigated all negative outcomes people may care about.

But the hyper vigilant universal vaccination advocates still have a myopic focus on zero COVID, which may be practically unattainable. While there may exist reason to believe so many lives can be saved simply by focusing vaccination campaigns on the most at-risk, it seems very misguided to narrowly focus on universal vaccination until after the low hanging fruit has all been picked.

The reaction to this article will be interesting to watch. It is really not the case that everyone in an age range has a probability of death if they get COVID. It is not the case that anyone in that age group who gets COVID spins the same roulette wheel and makes the same bet. Some people are more susceptible to death from COVID than others. It is our lack of knowing more about who those people are, inside of a large group, that causes us to rely on rates and probability statements. It will be interesting to see who discards those details and who takes them to heart.

The model was very accurate during the prediction window. After the prediction window ended, I released a second prediction graph for people to track on their own. The real world numbers eventually diverged, and the prediction (thankfully) failed. A review of that scenario will come in the near future - as it appears just as I released the first prediction Israel also started their first booster campaign (3rd shot). And generally, it takes 14 days for the vaccine to grant its full benefits. The deaths appear to have hit a hard ceiling just after my two week initial prediction window ended. They may be related.

Beta posterior distribution with Jeffreys Prior

Population estimates by age were given by data provided by ONS

CDC Comorbidities and other conditions

“Table 3 shows the types of health conditions and contributing causes mentioned in conjunction with deaths involving coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The number of deaths that mention one or more of the conditions indicated is shown for all deaths involving COVID-19 and by age groups. For over 5% of these deaths, COVID-19 was the only cause mentioned on the death certificate. For deaths with conditions or causes in addition to COVID-19, on average, there were 4.0 additional conditions or causes per death.”

Presumably the estimated number of lives saved through vaccination in your analysis is also provided that we don't develop (and actually deploy) more effective treatments for COVID in the mean time.

I'm not seeing the partially-vaccinated group in the analysis, yet that seems to be where most of the short-term risk from the vaccines is concentrated. It looks like deaths track first-dose and booster-doses; people who are 2-weeks-after-dose-2 or -after-booster have some protection (waning over time), but you have a significantly elevated risk following the 1st dose or booster. The net risk/benefit of the vaccines must include this high-risk period, and should include the loss of protection over time requiring boosters (with repeated high risk of injury/death). Also, a significant percentage of people are not able to get the 2nd dose, either because they had such a serious reaction or injury from the 1st that they will never get another one, or they died. People who get one dose and can't continue seem to be at much higher risk of dying over time, and that risk needs to be included.

I also object to the perversion of the language that calls 2-weeks-post-final-dose as "vaccinated", but doesn't include partially vaccinated. No one new to the discussion would have this expectation, and it is often unclear what is meant even when aware. Maybe we should call them "vaccinated-2-weeks-post-final-dose" or "vaccinated-2wpfd" to make this clear? Then we could call partially vaccinated "vaccinated-1-dose" etc.